Health Sciences Research

The battle against burnout

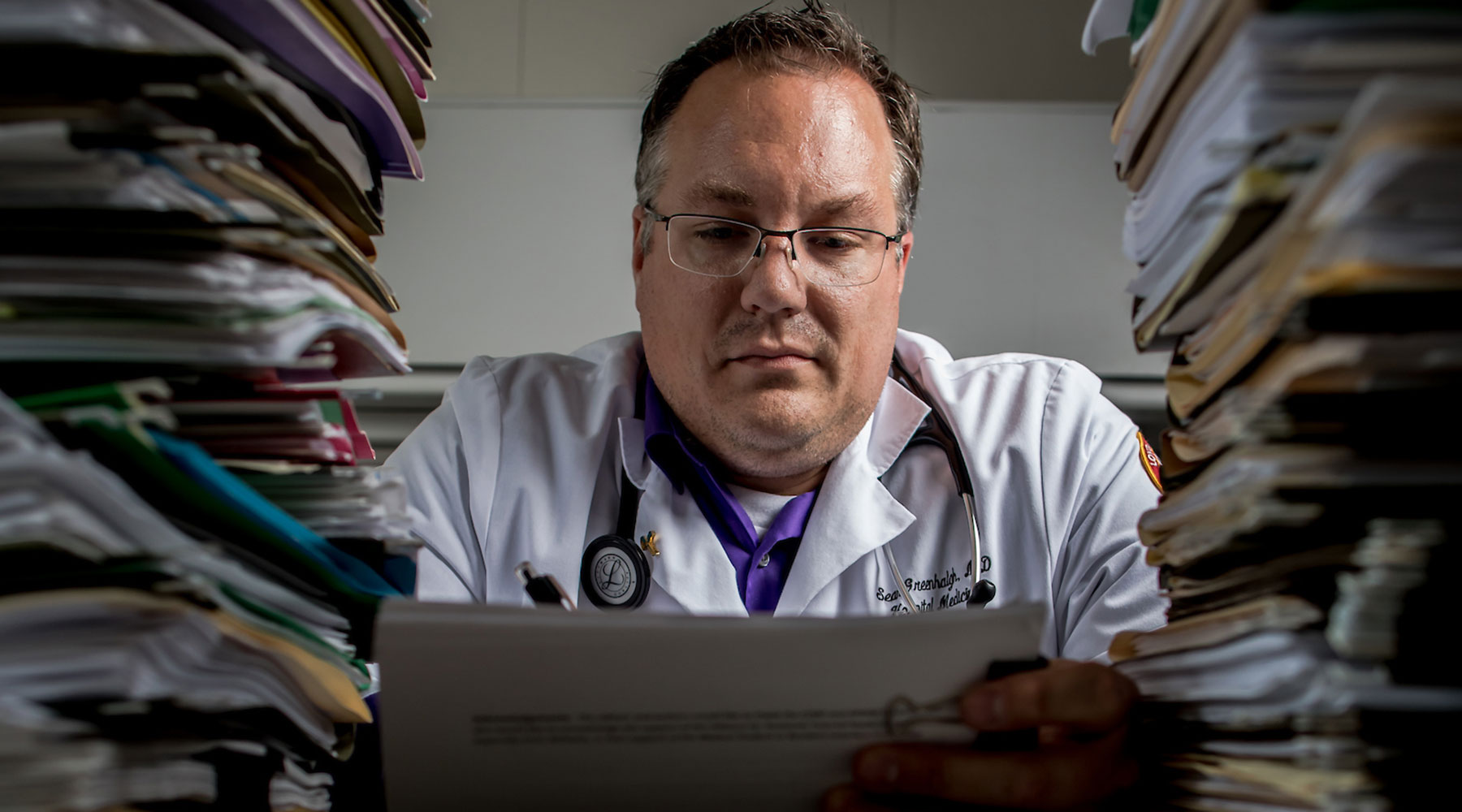

The wave hit hospitalist Sean Greenhalgh during his second year on the job. His department was overburdened, faced with too many patients and a constantly ticking clock. He and his fellow hospital doctors couldn’t even carve out 30 minutes to congregate over sandwiches and vent their frustrations. “I wasn’t doing the parts of the job that I enjoyed—sitting and talking to people, taking a deep dive,” he remembers. “It became about survival.”

His personal life was no less strained—Greenhalgh’s wife had delivered their first child a year prior, and another was on the way. He brought paperwork home with him, sprawling files across the kitchen table, worrying that every upcoming admittance would overwhelm him. Then he’d wake up panicked late at night, wondering if he’d logged a stray order incorrectly. All he could do was trudge downstairs to his laptop, bleary-eyed, and check again.

Every hour that Greenhalgh spent fretting was another he couldn’t rest or help his wife; he feared he was failing at both parenthood and medicine, two things he desperately loved. In moments of real weakness, he would daydream about teaching high school biology, before remembering he still owed some $200,000 in medical school loans. (Paying those down on a teacher’s salary wasn’t a realistic option.) He felt stuck, convinced he was the only person in the medical center wracked with self-doubt. Worst of all, he started to feel uncaring towards the patients who truly needed his help.