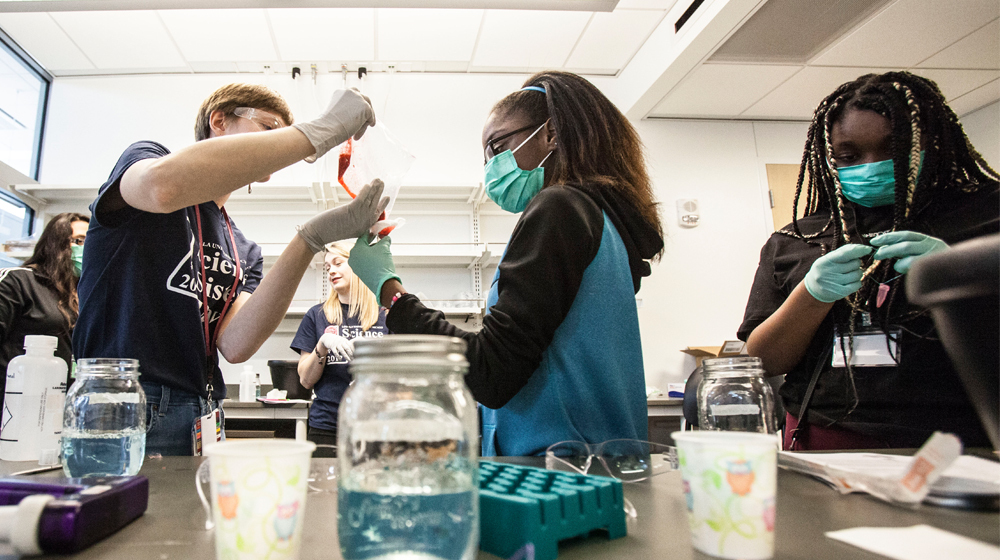

Women in STEM Mentoring female students

Breaking down barriers

At Loyola University Chicago, young women find the mentorship and camaraderie to bridge the gender gap in STEM fields.

Ariana Grymski knew from a young age that the hard sciences were for her. “I’ve always loved math,” she said. “In kindergarten, I’d ask my mom to get math books so we could play with them.”

Freshman year of high school, though, she got a B- in the subject. “I’m pretty sure I cried,” she said. “Math was kind of my thing.” After high school she decided to take a gap year, but didn’t want to go a full year without studying math so she signed up for a course online.

When she came to Loyola University Chicago, Grymski instantly felt a connection with Emily Peters, an assistant professor of mathematics and statistics. “She gets to know you on a personal level and makes you feel like you’re doing math with her,” said Grymski, a double math and physics major who expects to graduate in 2020. “I love going to her office hours because if you don’t understand something she’ll do whatever it takes to help you understand, like draw out notes or have you work on the board.”

It wasn’t until her sophomore year that Grymski discovered physics, and she took to it quickly. By the first month of her junior year, she knew she wanted to major in it. But her love of math has only grown under the guidance of Peters, and she’s come to enjoy the group work that Peters puts forward in class. “You really have to think about the problems she gives us and one person doesn’t dominate,” she said. “We all have to come up with ideas and help each other.”

A University-wide commitment

Grymski is one of many female students excelling in STEM—science, technology, engineering, and mathematics—at Loyola. On a national level, women tend to be underrepresented in these fields, as the U.S. Department of Commerce finds that women comprise 47 percent of the total U.S. workforce but hold only 24 percent of STEM jobs. And according to the National Center for Education Statistics, while women earn 57 percent of all undergraduate degrees they make up only 35 percent of undergraduate STEM degree recipients.

Loyola, however, is bucking that trend. A recent report by Emsi and The Wall Street Journal found that Loyola ranks seventh in the nation among colleges and universities for overall percentage of STEM graduates who are women. Using data from 2015-16, the report found that 344 of 706 STEM graduates at Loyola —or 48.7 percent—were women, putting the University well above the national average. The report also noted that Loyola has “had a constant presence at the top of the rankings in recent years.”

STEM programs at Loyola are incorporated in multiple schools and stretch across undergraduate, graduate, and continuing education programs, with nearly 30 undergraduate degrees and close to 40 graduate and continuing education programs focusing on STEM fields. Most recently, Loyola launched an engineering science program—with specializations in biomedical, computer, and environmental engineering—to round out the spectrum of STEM offerings.

#7

Loyola ranks among the top schools in the country for graduating women in STEM majors.

48.7%

of Loyola's STEM degree recipients in 2015-16 were women.

35%

of undergraduate STEM degrees nationwide are earned by women.

.jpeg)